by Christopher Paris

(Part one may be read here.)

Choking Dissent

As the recent AAQG / Cessna controversy shows, these organizations are not above cutting off any public discussion to shut down a conversation that doesn’t go their way. Over at the LinkedIn AAQG group, for example, ample conversations are held about counterfeit parts, the lawsuits and figures involved in them, as well as the problems that CB auditors face with the (mythical, I say) creature known as the “unruly client” who tricks the hapless aerospace auditor into a paper-only certificate. Those posts go unedited, unchallenged.

But on two recent occasions, people were reminded to “use OASIS” when discussing anything negative about CBs or the AAQG/IAQG itself. The message is simple: your access to free and open discussion is limited to criticizing only the people we don’t like, not us.

Ironic website message from the OASIS portal as of the day this was written.

Likewise, CB’s and AB’s routinely trot out their (required) complaint portals as a means for clients to raise issues. ANAB has an admittedly easy to use complaint portal on their site (here), but it doesn’t allow for anonymous or protected posting. The same for CB complaint systems, which required identification. This immediately and dramatically reduces participation because clients overwhelmingly fear retribution on the part of their registrar — in the form of having their certification withdrawn — if they file complaints.

CB’s have a “trick” they pull to ensure that complaints don’t get logged at all, because if they do they may be reviewed by ANAB or their accreditation body: they attempt to resolve everything by phone, so there is never a written record. And so registrars can point to remarkably low complaint levels, since the complaints they do receive are rarely documented.

Even procedures by accreditation bodies like ANAB and JAS-ANZ require that you submit a complaint first to your registrar, or they can decline to take action until you do. For those wanting to avoid a confrontation with their registrar, this presents yet another stumbling block, especially in cases like that of SGS and RABQSA, when the person named in the complaint won’t recuse themselves per accreditation rules, effectively locking up the entire process indefinitely.

Public Access on Private Property

The IAQG, ASQ, US TAG, IAAR and other organizations representing the offending power players talk a lot about open forums, typically held in public meetings at industry conventions. The reality is that access to these is not quite as public as they seem. First, there are large expenses with traveling to such conventions or gatherings, and then there are registration fees, hotel and rental car fees, etc. This immediately puts it out of reach for most people.

In Peru, when you want to get a question answered for anything significant, you have to drive to an office building and make an appointment. There is no “quick call or email” to get an answer, even though Lima has an advanced telecommunications system. It’s the culture.

So in the US we take instant access for granted. This makes the fact of how inaccessible these “public” events truly are even more glaring, and so much more like a developing nation, rather than a developed one. If I want to raise issues about ISO 9001 certifications I have to book a flight and hotel to Las Vegas, and hope I can get to ask a question at some point over a three day event? Really?

IAAR meetings are closed, and only approved speakers can attend. I gave a presentation to one a few years back, and was not allowed to sit through the balance of the meeting, and — this is where it gets weird — was actually directed to “not tell anyone” that I ever appeared. The paranoia in that room was tangible.

The ASQ events, US TAG 176 and AAQG/IAQG meetings are all run from pre-determined agendas which cannot be changed by attendees, and which does not allow for much (if any) time for open floor debates on problems facing end users. In all cases, the critical decision-making bodies within the organizations are closed, and not open for public input at all.

And of course, as we see with the AAQG LinkedIn event, access to social networking or public internet forums can be cut off on a whim by a moderator with a personal, political or professional agenda.

(UPDATE 3/16/2012: As if on cue, the AAQG has deleted its entire LinkedIn group, erasing all conversations and cutting off any discussion whatsoever. For more, click here.)

“Quality” Press

Unlike a democratic nation, there is no social expectation for an industry to have a critical, unfettered press. Robust industries, such as electronics and medicine, push ahead and accept criticism and debate within their ranks, publishing the debates, often “warts and all.”

The QMS world operates more on the “thin blue line” model of a corrupt police force, refusing to acknowledge any problems publicly, and chastising anyone who attempts to do so. Standards bodies, ABs and CBs are famous for conducting more closed door, inaccessible meetings than public forums, with possibly no greater example than the Independent Association of Accredited Registrars (IAAR), a semi-secret group of CB’s whose meetings are closed to the public, and (as I mentioned) whose minutes are never published, nor their actions reported on. I was told that the whiff of illegal price-fixing and collusion is so strong (competitors meeting in regular, closed door gatherings?) an attorney has to attend every meeting to keep the members in check. The question is, who pays the attorney?

So approaching the press would seem a good avenue. However, gaining access to the “quality profession” press is an impossible task for anyone not praising the CBs, ABs or usual players. Critical articles are only allowed when they point the finger at end users. Despite the very high-profile departure of the BSI VP, the main journal of the day – Quality System Update – did not report on it at all, possibly because BSI was a major advertiser. Dozens of Oxebridge press releases submitted to Quality Progress, Quality Magazine and other quality related magazines were routinely rejected if they included any criticism of registrars in general, never mind specific CB’s. After an article of mine on the benefits of AS9100 Rev C was published in Assembly Magazine, I approached the editors of their sister publication, Quality, with the suggestion to follow up with another article on some of the problems facing AS9100 users. They declined, saying, “we have a long-standing policy to avoid articles that criticize or denigrate [organizations].” In their minds, any critical analysis of a problem might “denigrate” someone, so only fluff pieces are allowed. And so the recorded history of the quality profession will state ours was a problem-free, perfectly operating machine, with never a flaw or blip.

At an open US TAG 176 meeting, then-chair Jack West openly admitted that the permanent, voting seat held by Quality System Update publisher Paul Scicchitano was for access — in order to ensure the US TAG continued to receive favorable reporting in QSU. Again: he said this in public, unapologetically and with total confidence. Sure enough, no negative reporting about the US TAG was ever published in QSU, despite dubious elections, overt profiteering and frequent anti-European commentary by the leadership.

Back in 2005, an article submitted by Oxebridge to the ASQ’s Audit Division Journal was rejected because it cited specific evidence of auditors violating accreditation rules, and named the registrars in question. The editor defended the decision by saying the article did not “meet ASQ’s stringent peer review process requirements.” In its place ran an article with the title “Listen Up: Stop Bitching and Complaining and Get With The Program! What’s Wrong With You Folks?!” which defended RABQSA’s controversial new auditor training program. When asked how its peer review process allowed swearing and insulting the readers in headlines, rather than including objective evidence in text, the editors did not reply.

Surveys

A great deal is made about surveys, which history tells us have a tremendously low response rate, and which provide dubious results at best. Again, fear prevents clients from issuing damning comments on registrar satisfaction surveys, and other major third party surveys are typically operated by organizations that either have a vested interest in the outcome, or rely on advertising dollars to publish.

Surveys also cannot guarantee the accuracy of the information or subsequent calculations, because none of the sponsored surveys are ever subjected to independent auditing. This includes the ever-so-dubious “ISO Survey” published by ISO every year, which reads as a fluff press piece to even the least discriminating eye.

The IAQG’s famous OASIS database is an online repository for filing complaints, which then generates survey data for internal consumption. The problem is that it rolls up so many of the other restrictions mentioned here, including the requirement for verified identification of the complainant, numerous limitations on the types of issues which can be reported, a restricted list of those who can complain, and no public availability or accountability for the resulting data. The end result is hardly a useful tool, but it makes for a great visual prop.

Selective Listening

A large problem facing Oxebridge in particular is the (invented) “requirement” that organizations and bodies within the QMS certification world cannot take feedback from a “consultant.” This is particularly egregious in that it is not substantiated with any rule, regulation or standard, and actually contradicts many such requirements which mandate feedback be accepted from all stakeholders.

CB’s routinely attempt to deny Oxebridge, and other consulting firms, from filing complaints on the behalf of their clients by citing this requirement. NQA once advised Oxebridge this was due to “confidentiality rules” even though we were acting, under contracts and NDA’s, with the client’s permission. Of course NQA never had a problem publicizing Oxebridge’s client satisfaction data when its scores were high, and only invoked the “no consultant feedback” rule when dealing with negative comments.

Similar positions against accepting feedback from consultants were made by SGS’s Zach Pivarnik, as well as reps from UL, BSI, Smithers, and Intertek. It is for this reason that Oxebridge typically escalates complaints to ANAB, because the CB’s refuse to accept it based on the source.

Oblivious to appearances or irony, the IAQG’s top committee on certification practices actually denies access for consultants or end users, and only allows for input from certification bodies… the very organizations they are allegedly governing. (“Use OASIS” is the mantra, again.)

Whistleblowing?

I am loathe to compare the efforts of Oxebridge and others to improve the state of QMS certifications and accreditations with whistleblowing — where people report problems of a far more serious nature, and face far more deadlier consequences — but it nevertheless rings awfully true when you compare the two. The reality is that those on the receiving end of a complaint almost to the letter react as if they are responding to a whistleblower, even if a particular complaint is trivial.

From Wikipedia:

Common Reactions

Ideas about whistleblowing vary widely. Whistleblowers are commonly seen as selfless martyrs for public interest and organizational accountability; others view them as “tattle tales” or “snitches,” solely pursuing personal glory and fame. Because the majority of cases are very low-profile and receive little or no media attention and because whistleblowers who do report significant misconduct are usually put in some form of danger or persecution, the idea of seeking fame and glory may be less commonly believed.

There have been many cases where punishment for whistleblowing has occurred, such as termination, suspension, demotion, wage garnishment, and/or harsh mistreatment by other employees. Many whistleblowers report there exists a widespread “shoot the messenger” mentality by corporations or government agencies accused of misconduct and in some cases whistleblowers have been subjected to criminal prosecution in reprisal for reporting wrongdoing.

In the cases I have mentioned in this series, you can see the similarities when CBs and others respond so negatively to complaints or feedback. Some things I’ve seen in the past 20 years:

- Registrar “blacklists” attempt to impact Oxebridge’s revenue by cutting off referrals.

- Physical intimidation through threats made by BSI’s ex-VP.

- Threats of oppressive “libel” lawsuits intended to stifle complaints before they can be filed.

- Ignoring the complaints completely, hoping the problem gets dropped entirely.

- Mis-characterization of the well-intended actions as misguided martyrdom, the work of a “nut” or someone trying to profit from scandal.

- Censorship actions by quality press editors, publishers, and (now) social network moderators in order to prevent discussion on issues.

- Attack posts and hurling of insults, in an attempt to “shoot the messenger” and discredit the source of a complaint.

- Pleading to take the issue “offline” by selling it as faster, but in reality to prevent a written record.

All of these actions, when looked at holistically, serve one goal: PREVENT SCRUTINY. There is no other explanation for any of these actions whatsoever.

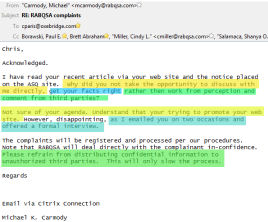

In his response to our 2005 complaint against RABQSA, Michael Carmody wrote a remarkably damning email that includes an example of almost every wrong way to respond to a complainant, one that could serve as a textbook study on power, arrogance, and denial in the face of criticism. Again, we don’t claim Oxebridge concerns are “whistleblowing” but Mr. Carmody pulls out every anti-whistleblower trick in the book. Click the thumbnail for a larger image of his email, from July 7, 2005:

Note the following highlighted points:

- AVOID THE WRITTEN RECORD: “Why did you not take the opportunity to discuss with me directly”

- CHALLENGE THE MERIT: “…get your facts right rather then work from perception …”

- IMPLY A CONSPIRACY MOTIVE: “and comment from third parties”

- DISCREDIT SOURCE: “Not sure of your agenda. Understand that your trying to promote your website.”

- AVOID THE WRITTEN RECORD (again): “I emailed you on two occasions and offered a formal interview.”

- PREVENT TRANSPARENCY: “The complaints will be registered and processed per our procedures…. Please refrain from distributing confidential information to unauthorized third parties.”

Every word in every sentence of Mr. Carmody’s response drips with the cynicism and anti-user loathing that flies in the face of the 8 Management Principles and the accreditation standards’ requirements for an “open and transparent” complaints handling process. By attacking and alienating both the complaint and the complainant — before he’s even started an investigation — he seeks to shut off the feedback entirely, rather than welcome it.

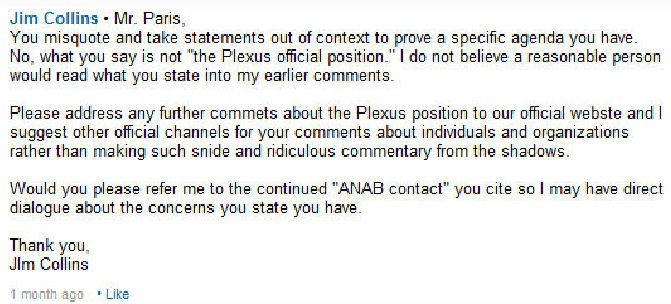

See also the response from Plexus International’s Jim Powell, which features the anti-whistleblower tactics of attack, discredit, assign motive, deny and hide, as seen in this screenshot from LinkedIn:

The two responses were written by two men from different countries, six years apart, representing different organizations, but they read as if they could have been sent by the same man. And remember: these are the organizations training the auditors!

All of this is in direct opposition to the spirit and language of the standards these organizations not only represent, but also the ones most of them are accredited to. If this latter statement were untrue, would we see any of the examples presented above? Instead, we would see robust, vigorous and public discussion, with active participation by all segments and stakeholders, with nary an insult, attack or invented motive in sight.

Christopher Paris is the founder and VP Operations of Oxebridge. He has over 35 years’ experience implementing ISO 9001 and AS9100 systems, and helps establish certification and accreditation bodies with the ISO 17000 series. He is a vocal advocate for the development and use of standards from the point of view of actual users. He is the writer and artist of THE AUDITOR comic strip, and is currently writing the DR. CUBA pulp novel series. Visit www.drcuba.world