ISO likes to publish stuff. It’s their job, after all, as a not-for-profit commercial publishing company. (They are not an NGO or charity, despite their claims to the contrary.) And some of the things they like to publish are rules for how to publish other things. Rules with rules, or as Frank Herbert said, plans within plans.

Yes, ISO has official-looking rules for developing, writing, and publishing standards. These are primarily codified in two documents (which you can find here):

- ISO / IEC Directives Part 1: rules for developing international standards (committee work, etc.)

- ISO / IEC Directives Part 2: rules for writing international (content, structure, etc.)

Oddly, even though Part 2 is the one that gets into the weeds about writing standards, Part 1 includes the much-loathed “Annex SL” content that directs mandatory text and structure for management system standards. Right now, the two documents total over 270 pages, so they are a dense set of requirements that appear, on their face, to be rather important and legitimate.

Here’s the rub, though. They were initially written to shut up the World Trade Organization (WTO), who felt ISO was infringing on free trade and dipping closely into writing actual laws without — you know — actually being a government. So it was important that ISO make these documents appear legitimate and binding, while in the real world, they are just fanciful ideas that go entirely unenforced. About ten years ago, or so, ISO realized that the WTO had no real power over it, and so they stopped caring what they thought, and ISO started doing whatever it wanted.

So let’s look at some of the development rules that ISO not only broke with ISO 9001:2015, but they are entirely juggernauting through with the next version, ISO 9001:2026. These are from the Part 2 directive set.

Part 2 Section 4: Objective of Standardization:

Documents shall be: consistent, clear and accurate [and] be comprehensible to qualified people who have not participated in their preparation

That point is so demonstrably and hilariously false, in the context of ISO 9001, I hardly need to elaborate. So I won’t.

Part 2 Section 5.4: Performance Principle

Whenever possible, requirements shall be expressed in terms of performance rather than design or descriptive characteristics. This principle allows maximum freedom for technical development and reduces the risk of undesirable market impacts (e.g. limiting development of innovative solutions).

As I mention often in my training, ISO standards are intended to tell you what to do, but cannot tell you how to do it. Regardless, ISO 9001 violates this in many, many ways that often go unnoticed to the casual reader. Such as:

- ISO 9001 dictates two specific sentences that must be included in your Quality Policy, essentially writing it for you.

- ISO 9001 dictates you shall have “a” design process, suggesting you can’t have more than one.

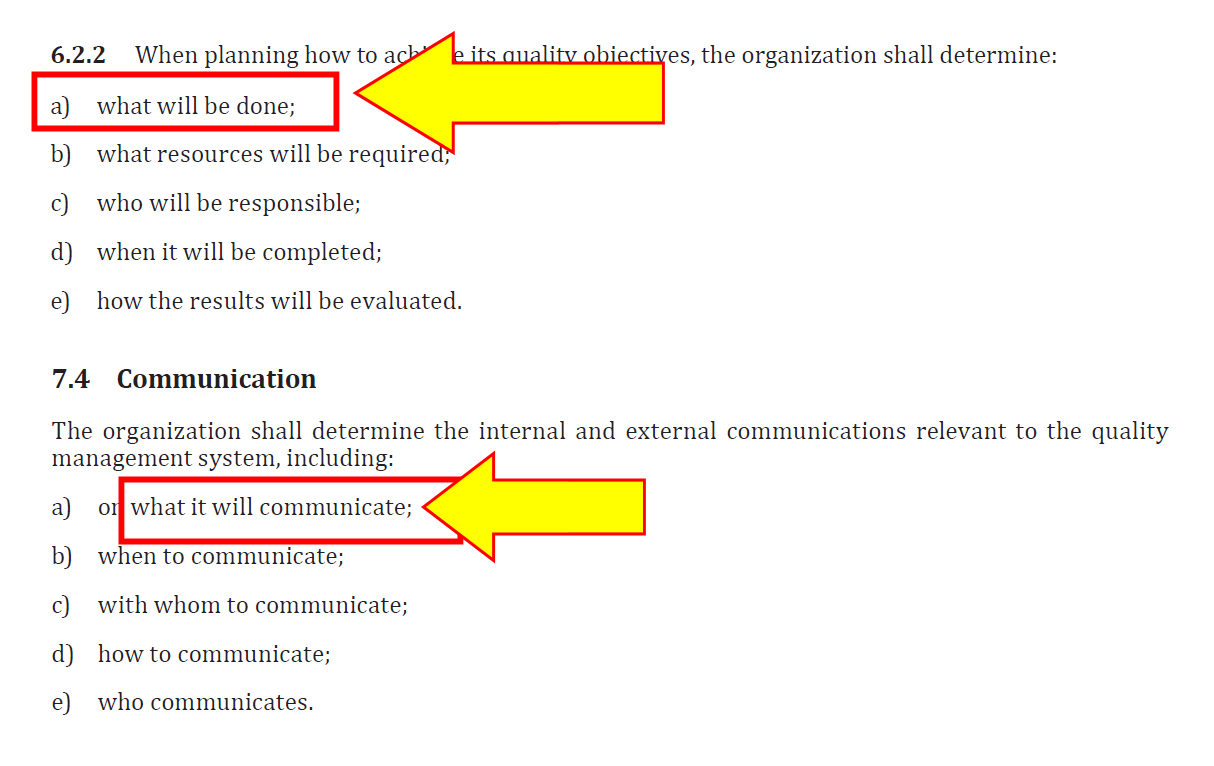

Then there are the cringeworthy “who-what-when-where-how” clauses, where TC 176 couldn’t even be bothered to tell you what to do. Instead, they suggest you fill in the blanks. Like these:

Now, most of these just go ignored because readers and consultants recognize that they are stupid. The Quality Policy one, however, gets enforced by third party auditors, so we have to grin and bear that one.) But in all of these cases, the rule on ensuring “requirements shall be expressed in terms of performance rather than design or descriptive characteristics” is violated.

Part 2 Section 5.5: Verifiability

Requirements shall be objectively verifiable. Only those requirements that can be verified shall be included.

While this was largely met with ISO 9001:2000, the 2015 update threw this idea out the window. Concepts like “risk-based thinking,” “understanding the organization and its context,” and the entire clause on “leadership and commitment” present requirements that cannot be objectively verified by anyone other than a psychic, and psychics aren’t real. This is made worse by ISO’s decision to dumb down ISO 9001 for lazy companies, and strip out nearly all the requirements for documents and records — things that could be used to “objectively verify” a requirement. Now, you need only “think” about risk, and you ‘ve met the literal text of the standard.

This causes no end of nightmares for those of us going through third-party audits. Auditors require evidence, but the standard does not. So, auditors demand things that are not required by the standard (a risk register, a training matrix, a preventive maintenance program, etc.) They’re not allowed to do that, but no one stops them. It’s a mess.

Part 2 Section 5.6: Consistency

Identical wording should be used to express identical provisions. The same terminology should be used throughout. The use of synonyms should be avoided.

Because ISO 9001:2015 was never edited before publication, due to ISO’s mad rush to get it published, the upcoming ISO 9001 revision is likely to simply carry over that standard’s errors. There’s no sign that ISO 9001:2026 is undergoing editing either. There are three cases where ISO 9001 violently ignores the requirement for consistency, causing tremendous confusion:

Up until clause 8.6, the term “monitoring and measurement” is used to replace the older term (from ISO 9001:1987) of “inspection and testing.” Throughout the standard, it is clear that “monitoring and measurement” is used to define the actions taken to ensure products meet requirements. They even have a clause on “monitoring and measurement resources,” referring to inspection and test equipment.

Then, however, in clause 8.6, ISO drops the term entirely, replacing it with “release” and “planned arrangements.” 8.6 is the actual clause on inspection and testing, but never uses the words. It doesn’t even use the words “monitoring and measurement.” When it says you must have records of “release,” the clause reads like a shipping requirement. It makes no sense.

Then, it gets worse. In clause 9, ISO re-introduces the term “monitoring and measurement,” but this time it doesn’t mean inspection and testing. For clauses 9 and 10, it means a more traditional meaning of simply monitoring and measuring data, from all sources, not just inspection and testing.

Now, look at a single sentence represented by clause 9.2.2 on internal auditing. Yes, that’s one sentence. In it, however, the authors flop back and forth — three times! — referring to internal auditing as a “process,” then a “program,” and then a “process” again.

Of course, the term “opportunity” is used in various contexts. Clause 6 thinks of them as a formal replacement for preventive action, but by clause 10, the term is used to refer to casual suggestions made by top management or in other scenarios.

Finally, ISO is an absolute mess on the word “process” itself. Whereas clause 4.4 clearly states “the organization shall determine the processes needed for the quality management system,” the authors begin tossing the word “process” around in every other context imaginable. For example:

- They refer to internal auditing as a process (as I said above)

- They require a “design” process

- They make a vague reference to undefined “business processes“

- They refer to “outsourced processes“

Stupid CB auditors — of which there are many — will often force a client to invoke all the controls of 4.4 for the places where ISO drops the word process. For example, they will demand that you have a standalone design process, or a standalone “internal audit” process, because of these wording errors. That contradicts 4.4, which says the organization determines its processes, not the authors of the standard. Again, this causes conflict during third-party audits.

Part 2 Section 5.7 Avoidance of Duplication and Unnecessary Deviations

Before standardizing any item or subject, the writer shall determine whether an applicable standard already exists. If it is necessary to invoke a requirement that appears elsewhere, this should be done by reference, not by repetition. As far as possible, the requirements for one item or subject should be confined to one document.

Remember how many definitions ISO has for the term “risk“? Case closed on this one.

Part 2 Section 7.1: Verbal Forms for Expressions of Provisions

The user of the document shall be able to identify the requirements he/she is obliged to satisfy in order to claim conformance to a document. The user shall also be able to distinguish these requirements from other types of provision (recommendations, permissions, possibilities and capabilities).

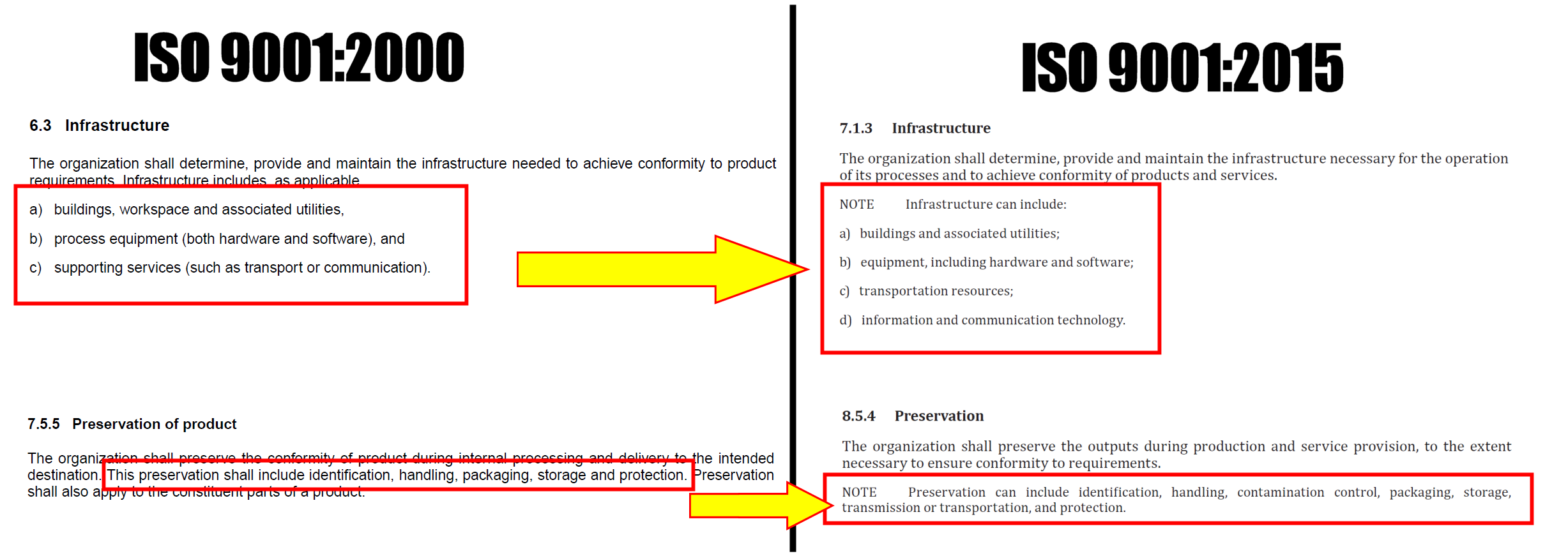

One of the greatest sins of ISO 9001:2015 is how, for no reason whatsoever, the consultants who wrote the document took perfectly fine wording from the prior edition of the standard and moved them around. This was all for ego: the “new” authors wanted to show they were smarter than the “old” authors, but screwed everything up in the process.

Look at how they moved — again, for no reason at all! — the requirements in these clauses into “notes” in the new edition.

Under the new standard, auditors are forced to audit — and write nonconformities — against the notes. Again, the prior language was just fine. The change was never justified.

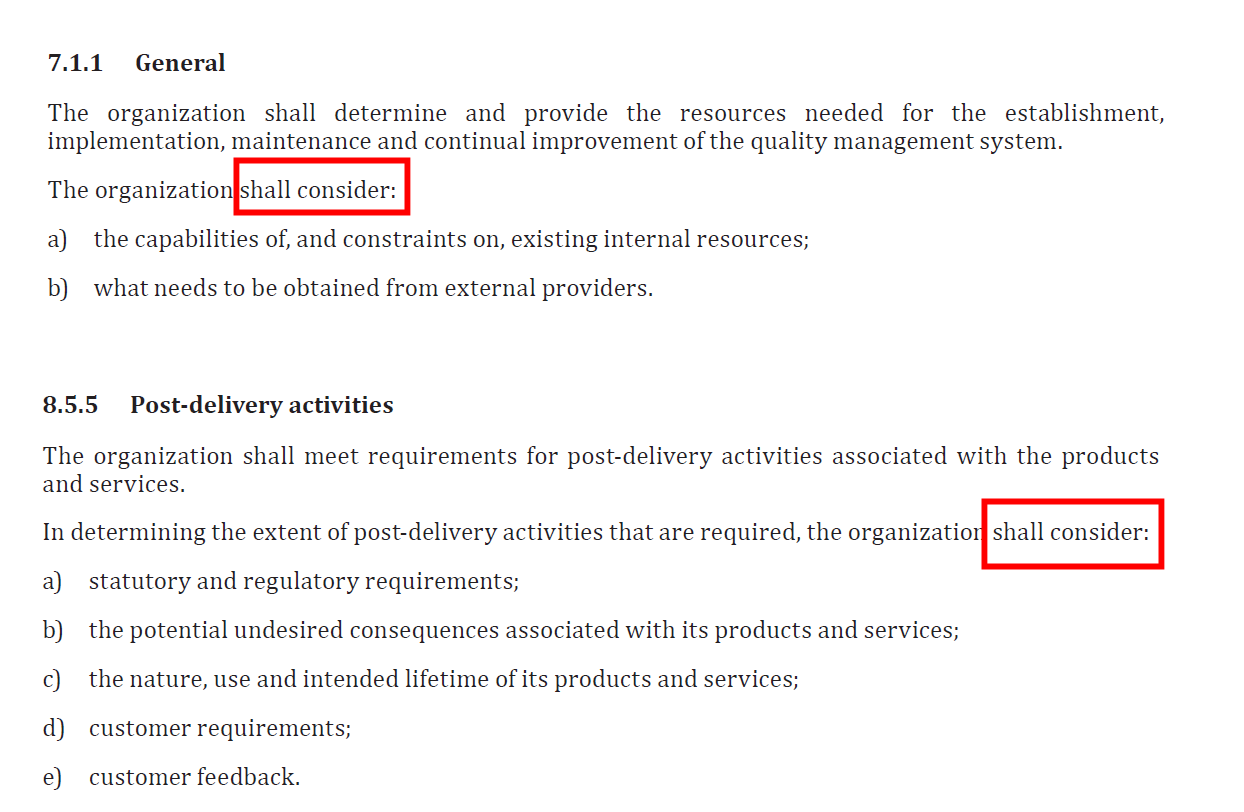

Then we have the “shall consider” conundrum. In the 2015 version, the consultant authors of ISO 9001 started using the term in the requirements portions of clauses. “Shall consider” appears in nine different places, such as these:

Here’s the problem. First, the word “shall” indicates a mandatory requirement, per the ISO directives themselves. Those same directives don’t define “consider,” so we have to rely on the dictionary instead. In all cases, the word si used to refer to “think” about a thing and then weigh whether or not to take action. Here’s Merriam Webster:

To think about carefully: such as (a) to think of especially with regard to taking some action [or] (b) to take into account

By combining a mandatory command (“shall“) with something that results in an optional decision result (“consider“) the two terms negate each other. As a result, where ISO 9001 says, “When addressing changing needs and trends, the organization shall consider its current knowledge…,” a valid response would be, “We considered it and decided to do nothing.” As a result, anywhere you see the term “shall consider,” this actually prefaces an entirely optional bit of text that should have been put in a note, but was jammed into the requirement. The opposite of the last problem I discussed.

In the end, the authors of ISO 9001:2015 (and the upcoming revision) have no clue what a requirement is compared to a suggestion, and they jumble them all around to the point of creating absolute chaos. And, therefore, the user is unable “to distinguish requirements from other types of provision,” as required by the Directives.

Part 2 Section 8.5: Linguistic Style

To help users understand and use the document correctly, the linguistic style shall be as simple and concise as possible. This is particularly important for those users whose first language is not one of the official languages of ISO and IEC.

One of the phrases that bothers me the most in ISO 9001 — and it’s been in prior versions, too — is “deal with.” This phrase has a unique meaning in English, but doesn’t translate well into other languages. In Spanish, for example, the closest translation is “tratar de…” which literally means “treat.” “Deal” in Spanish is largely understood in the context of dealing cards. This is true in other languages as well; in Chinese, the term 处理 (chuli) is used, and is meant to “process” something.

And yet, ISO 9001 insists we “deal with” nonconforming products and then “deal with the consequences” of other nonconformities. It sounds like the Mafia wrote it.

The Fix

So, how can ISO fix this? First, by acknowledging the problem. ISO must realize that ISO 9001 was a pretty good product back in 2000 and could have been damn near perfect with a few fixes. Instead, it replaced the development team with a bunch of unqualified consultant hacks, handed 1/3 of the drafting to the non-elected, non-subject-matter-expert TMB, and cut the in-house editing staff. It skipped major steps like proofreading and translation to get the standard published early, just to make money.

If ISO acknowledged these flaws — and the fact that most people think ISO 9001:2015 is the worst version of the standard in its entire history — it could start to repair the problems. This means:

- Fire the consultants. Enforce existing rules to ensure that TC 176 is comprised of a fair balance of end users along with other stakeholders. Stop the near 100% participation by private consultants who have a reason to make things complicated (to sell their services).

- Fire the TMB. Disallow the TMB from writing any text at all, since this violates WTO rules, ISO rules, and every other rule under the sun.

- Bring back real editors who know how to not only read and edit documents, but also understand the ISO Directives.

- Slow down – if a document is flawed, take time to edit it before publishing it.

- Put back in the mandatory translation steps. Non-English speaking countries should be able to review and vote on standards in their language, not English. That would catch mistakes that might not be apparent in English.

- Obey the Directives. If a draft violates them, it goes back for another round of edits.

- Fire disobedient Committee Members. If a committee just can’t bring itself to obey the directives, get new members; replace the leadership.

- Perform a final White Glove edit prior to FDIS.

This is not hard stuff. It’s only hard because ISO, under the corrupt Sergio Mujica, is being run as a for-profit publishing house. That’s because his personal salary is at stake, and Mujica probably wants a few more houses.

But because we live in Hell now, none of that will happen, and TC 176 consultants are working hard to ensure that ISO 9001:2026 is even worse.

Christopher Paris is the founder and VP Operations of Oxebridge. He has over 35 years’ experience implementing ISO 9001 and AS9100 systems, and helps establish certification and accreditation bodies with the ISO 17000 series. He is a vocal advocate for the development and use of standards from the point of view of actual users. He is the writer and artist of THE AUDITOR comic strip, and is currently writing the DR. CUBA pulp novel series. Visit www.drcuba.world