ISO 9001 in the US is on the decline, and there are many places to lay blame. The infrastructure surrounding ISO 9001 certification scheme is a complex organism, comprised of relationships between clients, consultants, auditors, certification bodies (CBs), accreditation bodies (ABs) and standards authors. Each party has a role to play in ISO 9001’s demise, and each one has a role to play in its repair. I want to be clear: in this piece I am not suggesting that ANAB — one of the world’s largest and most influential accreditation bodies — can fix this single-handedly. But it is in a very strong position to do some very real good, in very short order.

Since ANAB controls the accreditation of registrars, their work is almost entirely focused on what they can do to improve the perception of ISO 9001 by enforcing established accreditation rules, through oversight audits of the CBs they accredit. Let’s take a look.

1: ADMIT THERE IS A PROBLEM

First off, ANAB has to admit that there is a problem with ISO 9001, and its reputation. This doesn’t mean running public press releases announcing that the sky is falling. (That’s my job.) They can have secret, internal meetings on the matter, and strategize as to what their role is, and how they can work to help reverse things.

ANAB is a highly secretive organization, with its public face a tightly controlled, highly managed image. We don’t know for sure if they admit there is a decline in ISO 9001’s perception or not. But an examination of their public actions shows that they are not taking steps to correct problems under their control, so in the vacuum of information we are left to assume they fail to “get it.”

If they do “get it,” then this list just got shorter. That’s good news.

2: VERIFY OBJECTIVE EVIDENCE

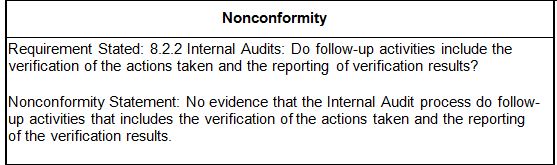

It’s not great to be left with a set of nonconformities after a registrar’s ISO 9001 certification audit, but it’s impossibly frustrating when you don’t understand what the auditor was looking at, and you can’t fix the problems as a result. Of the more than 200 audits I have witnessed alongside clients, the overwhelming majority of those that resulted in a nonconformity lacked objective evidence. Here are two examples, from actual registrar final audit reports:

In this case we can see that the auditor did not record which audit reports he looked at. In fact, the auditor had also examined corrective actions resulting from the audits, and he did not record those either. The ultimate response was that, after scouring through records and guessing as to what he was looking at, the client proved that the corrective actions themselves (not the audit reports) contained the necessary follow-ups, and the entire nonconformance was dropped. It was a lot of wasted effort.

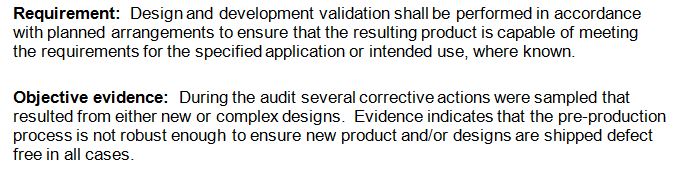

Here’s another:

Once again, there is no actual evidence recorded. We do not know which designs the auditor examined, nor the corrective actions reviewed. Furthermore, it concludes a problem exists based on a purely subjective opinion (“not robust enough”) which cannot be quantified.

Without evidence, the client cannot perform immediate containment. The client cannot perform proper root cause analysis, and any fix is likely to be temporary and not particularly useful. This leads the client to feel as if they are wasting time on meaningless trivia, and raises questions as to the abilities of auditors.

The thing is, it’s easy to spot. ANAB merely needs to assess audit reports and look for numbers: revision numbers, CAR numbers, file numbers, dates, etc. Normally, records are enumerated in some way. If a finding is lacking some kind of number, it’s usually lacking objective evidence.

(That’s not the best method, admittedly, but I’m trying to make it easy on them.)

3. CHECK AUDIT SCHEDULES

Another dirty secret in the ISO 9001 world is that audit schedules are a sham. Specifically, they are often not provided prior to the audit, and if they are, they are often not followed. This makes planning impossible on the part of the auditee, and even more frustrating when the auditor complains that top management isn’t available when needed, because they never provided a schedule.

To verify this, ANAB need merely check email records to see when — or if — the audit schedule was actually provided to the client ahead of the audit in a reasonable amount of time, per accreditation requirements.

The other facet of this is near thievery. Routinely, auditors finish the audit ahead of schedule, and cut out early on the last day. The final audit report shows a full day of auditing, but the auditors have already left by noon. Clients don’t know this is a problem, and may even be relieved to have the audit completed early. But it’s still theft: the client is paying for the established number of days, and auditors that leave early, and then lie on the final report, are effectively stealing the client’s money. In addition, this results in a poorer audit, as it is less comprehensive.

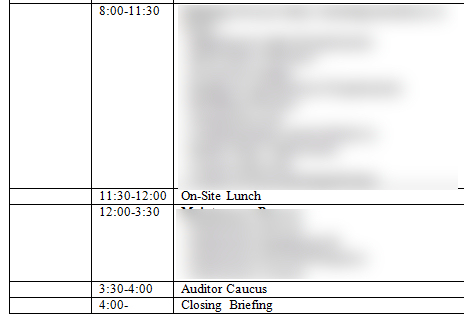

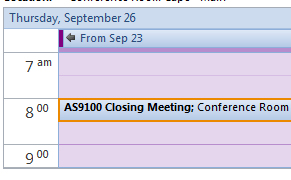

Here’s an example. Below we see the actual CB schedule provided to the client, with the time scheduled for the closing meeting. Notice that it is 4:00 PM (last line, at bottom.)

Now look at the calendar event established for the meeting by the client … 8 AM. The client paid $1300 for an entire day of auditing they never received, but the final audit report sent back to the home office still reflected a 4 PM end time. This means the auditors intentionally falsified the audit report.

Admittedly, comparing audit schedules vs. a client’s Outlook calendar is impossible for ANAB to do. Instead, however, they can compare the official audit schedule with the auditor’s travel records. If the auditor left the plant before the closing meeting was scheduled, it’s a simple red flag. Not to mention that if ANAB started fussing around auditors’ emails, you would see a nearly immediate improvement in service.

4. STOP CB CONSULTING ONCE AND FOR ALL

This one is a tough sell to ANAB. They truly believe that when an auditor provides suggestions it helps the customer. They ignore the fact that such suggestions are almost always a form of consulting, no matter how they are worded, and that as soon as a company accepts the suggestion, they enter into a conflict of interest with the registrar. If the client acts on the suggestion, this predisposes the auditor to a positive slant when they come back, as they will see their own handiwork materialized. The auditor is now auditing his own work.

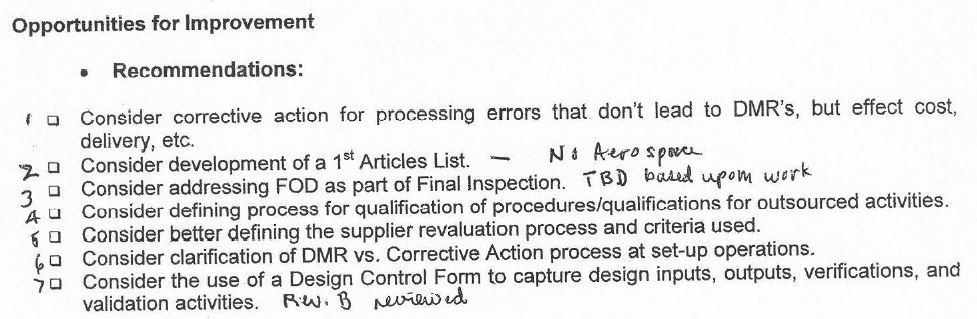

What’s more frustrating is how ANAB can tolerate decades of “opportunities for improvement” which are clearly “specific solutions” prohibited under the accreditation rules. Let’s look at just two examples.

For this first one (ignore the handwriting, it was added by the client), notice how the second bullet point did not suggest a generic improvement to the first article process, but actually suggested creating a form, and even suggesting a title for it (“1st Articles List.”) He does the same with 7.3, suggesting the client create a form called a “Design Control Form” to record design information. Going on, the auditor suggests the very specific solution of adding a FOD (foreign object debris) check to the final inspection, rather than merely suggest that “FOD inspections could be improved.”

Auditors are trained to add the words “consider” as a get-out-of-jail-free card, under the bogus assumption that by making the specific solution optional, it’s no longer specific. But that’s not what accreditation rules prohibit. It is not the optional nature that ISO 17021 has an objection to, it is the specificity which turns an OFI into a consulting activity.

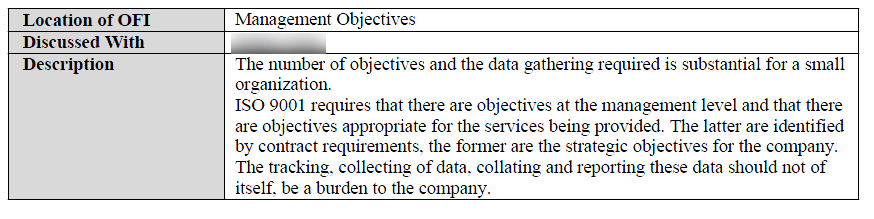

Here’s another. In this case the auditor makes the astounding suggestion that a client is measuring too much. Not only is this based on pure, subjective opinion, it violates the spirit of ISO 9001, and risks putting the company in jeopardy should they take the advice and another auditor later cites them for not having sufficient objectives. The OFI goes on to provide direct consulting by training the client on the auditor’s own personal interpretation of ISO 9001, and how to implement it (“the latter are identified…”). That this interpretation is not actually grounded in ISO 9001 requirements adds more frustration.

ANAB needs no special advice on how to spot these examples of prohibited consulting; they need merely read the reports, and begin to understand that such things add subjectivity and conflicts of interest that undermine the entire accreditation scheme. To date, they simply elect not to.

5. ENFORCE “TECHNICAL EXPERT” RULES

ISO 17021 requires that every CB have on staff “technical experts” (TEs) for the range of services and industries for which it provides certification. Furthermore, the accreditation rules require that such TEs be trained and have demonstrable competence. This means a CB without a TE for electronics cannot provide certification services for electronics companies, because the CB lacks the necessary technical expertise.

As soon as you read that, I am sure you concluded that the rule is routinely ignored, or at least stretched to the near-break point. You’re right. In order to provide certification services to the maximum number of possible clients, the “expertise” of on-staff Technical Experts is exaggerated or even fabricated outright. I once discovered that one CB’s TE for food manufacturing was deemed competent because his daughter worked as a waitress in a restaurant. Another CB claimed a flight attendant was a suitable TE for aircraft repair.

What’s the impact? TE’s are supposed to ensure that auditors, review committees and other CB activities are in line with each industry’s technical requirements. Without proper industry experts, there is no one to flag bogus auditor nonconformities, no one to spot inappropriate suggestions for improvement, and no one to consider the impact of bad audits on a given industry.

Now, it is nearly impossible for every CB to have a TE on staff for every industry it serves, given the shrinking market size and CBs’ dwindling staff. That’s the defense, anyway. But it’s no excuse.

Instead, registrars should scale their services to match their expertise, rather than “pad their resumes” by exaggerating the skills of existing staff to allow for them to serve every possible industry. If they cannot find a food expert, they shouldn’t offer ISO 22000 services. If they have no aerospace experts, sorry, no AS9100.

Doing the above would not only benefit the end users of ISO 9001 and related standards, but force improvement on the CBs, as well. Beyond that, of course, it would ensure ANAB had a future-proof industry to continue serving. As it stands, both CBs and ABs are losing market share and going out of business because of a perception that certification is a scam. Enabling the practices above — some of which may be illegal — only hastens the demise of their own companies. In another ten years, there may not be an ANAB to even read this.

If ANAB wants to live up to its mandate to ensure the validity of accredited certifications, and to stop the growth of unaccredited certificate mills, reverse the declining numbers of ISO 9001 certificates, and regain the trust of organizations worldwide, these five steps are an easy way to start. They simply ask that ANAB merely enforce the rules it has now.

Christopher Paris is the founder and VP Operations of Oxebridge. He has over 35 years’ experience implementing ISO 9001 and AS9100 systems, and helps establish certification and accreditation bodies with the ISO 17000 series. He is a vocal advocate for the development and use of standards from the point of view of actual users. He is the writer and artist of THE AUDITOR comic strip, and is currently writing the DR. CUBA pulp novel series. Visit www.drcuba.world