ISO 9001 discusses the idea of “processes” in a wide variety of ways. This is a bit frustrating, since the standard opens up (in cluase 4) by mandating the “process approach” to managing a quality management system (QMS), but then discusses the idea of “processes” in vairous different contexts throughout the rest of the standard, many of which don’t have anything to do with the process approach. So if you get confused, it’s the fault of ISO9001’s authors, not your reading comprehension skills.

The standard then discusses two additional concepts: special processes and outsourced processes. In prior editions of ISO 9001, the controls for each were more clearly defined; in the muddy ISO 9001:2015 version (and the upcoming 2026/2027 version), they are poorly defined, and one of them isn’t even named outright at all.

Outsourced Processes

Outsourced processes are referenced twice. In clause 8.1, it says, “the organization shall ensure that outsourced processes are controlled.” It then points you to clause 8.4, the purchasing clause, but that section never again uses the term “outsourced processes.” So if you were expecting to see 8.1 point to something about the concept in 8.4, you won’t find it.

Instead, 8.4.1 opens up with a three-bullet list of examples of when the controls defined in 8.4 apply (and thus where they do not.) One of those bullets refers to “a process, or part of a process, is provided by an external provider as a result of a decision by the organization.” It would have been nice if ISO 9001 had added a parenthetical or note somehow tying that back to the “outsourced process” reference in 8.1, but we can’t have nice things. But that is what they are talking about.

Other than that, there are no further clear requirements related to the concept of outsourced processes.

So what does it mean? First, in plain language, an outsourced process is anything that your customer would expect you to do, but which you then subcontract out to someone else. For example, you are a machine shop and you have to not only machine parts but also paint them. But you don’t have a paint shop, so you outsource the painting. In that case, “painting” is an outsourced process for you.

This is crucial to understand because the outsourced paint shop can screw up your hard work and add defects to the products. If so, you’re still to blame — at least from the customer’s point of view. So you have to control the quality of the work being done by the outsourced process provider — in this case, the paint shop. You can’t tell your customer, “Well, it’s the paint shop’s fault, not ours.” That line of defense won’t work.

8.1 and 8.4.1 are demanding that you ensure control over these providers and still take responsibility for the quality of their work.

So how do you do that? Typically, through contractual flowdowns via your purchase order or contract with the outsourced service provider. Then, you will also do certain things when the processed parts come back to you, such as visual inspections, testing, or other checks. You have to verify the work of that third-party provider somehow. How you do it is entirely up to you, but you have to do something.

A real wrinkle, though: technically, ISO 9001 does not require a contract or purchase order to “communicate” your requirements to the supplier. In fact, TC 176 issued an official interpretation reminding people that you don’t need to have any written record at all of your order. This is batshit crazy, but TC 176 has no idea how purchasing stuff works. So how do you “flow down” requirements verbally? Well, you don’t: you put them on your purchase order, regardless of what TC 176 thinks.

One quick additional point: if you outsource QMS internal auditing or calibration, those are outsourced processes, and you must have controls for them. So, for the clients who hire Oxebridge to do their internal audits, for example, we make sure they have controls in place to verify our work.

Special Processes

Now let’s examine special processes. This concept gets more frustrating since the term isn’t used at all in the standard, but it does have a requirement associated with it. There is no way a reader of the 2015 version would know that the requirement is referring to special processes.

Here we jump to a very obscure and poorly-worded bullet in 8.5.1 (f):

The organization shall implement production and service provision under controlled conditions. Controlled conditions shall include, as applicable: … (f) the validation, and periodic revalidation, of the ability to achieve planned results of the processes for production and service provision, where the resulting output cannot be verified by subsequent monitoring or measurement.

To be fair, the prior editions of ISO 9001 (2000/2008) didn’t name them “special processes” either, but did at least give details on what, exactly, you need to do to “validate” them. That standard required:

- defined criteria for review and approval of the processes,

- approval of equipment and qualification of personnel,

- use of specific methods and procedures,

- requirements for records, and

- revalidation.

We have to go back all the way to ISO 9001:1994 to find a note that clarified this, saying, “Such processes requiring prequalification of their process capability are frequently referred to as special processes.”

Why ISO removed that note is a mystery, since the manufacturing industry continues to use the term nearly universally.

So what is a special process? The official definition, put into plain language, says that it’s anything you do that you cannot later inspect or test. This might be because you lack the necessary equipment or ability to check it; for example, it requires X-ray inspection, and you don’t have the X-ray machinery. Or, it might be a case where something you do after the process prohibits you from inspecting it; for example, you machine a tube, but then weld the ends, so you cannot check the cleanliness of the interior of the tube since it’s welded shut.

This gets tricky because various industries, automotive and aerospace among them, have very set ideas on what processes are to be deemed “special processes,” and they don’t care if you can inspect them or not. These include:

- Welding / brazing / soldering

- Plating / chemical finishes

- Painting / dry powder coating

- Nondestructive testing (NDT)

- Precision cleaning

- Epoxy

- Heat treat

In some of those cases, you might be fully equipped to perform inspection and testing, but your customer or your industry requirements (specifications) will demand you treat them as special processes anyway. Thus, you need to validate them.

Validation, put in simple terms, is doing more of what you can do. This means:

- More operator qualification: training, certification of those doing the work

- More process controls: for example, calibration of process equipment (ovens, tanks, gauges, etc.)

- More procedures: define the steps for the work in as great a detail as possible, to ensure consistency

- More inspections or tests for what you can do: for example, 100% visual inspections on the processed parts

- More records: certifications, lab tests, reports, etc.

Wherever possible, it’s best ot use industry standards to control special processes. So, if you do chrome plating, do it per an applicable AMS specification, like AMS 2460. For welding, you might apply AWS specifications, and for soldering, IPC standards. This removes your responsibility to develop the methods and ensure you are working to industry-approved methods.

In the aerospace industry, we have Nadcap accreditation for special processes. If you’re AS9100 certified, and if your customer requires it, you may also have to get Nadcap accredited for each special process you do in-house. That is a separate audit, not of your entire QMS, but of the specific manufacturing processes involved; however, you must have AS9100 or an equivalent in place before you can even get your process Nadcap accredited.

I’m not an automotive expert, but I suspect there’s some equivalent under the IATF 16949 scheme.

The Overlap: Outsourced Special Processes

Now, where this gets even more confusing is that often a company outsources its special processes. That means some outsourced processes are also special processes. But the opposite is not true: not all outsourced processes are special processes.

Regardless of what you outsource, you have to apply controls on the third-party provider. If you outsource a special process, however, you will have to flow down even more controls. For example, you may require your third-party plating house to be Nadcap accredited. Other additional controls on providers of outsourced special processes might be:

- Requirements for certifications and test reports

- Evidence of operator qualifications

- On-site supplier audits (you audit their facilities directly)

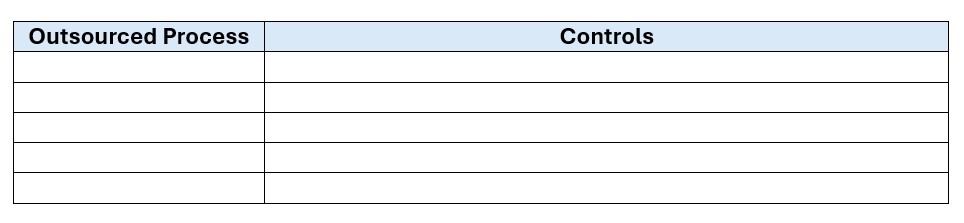

This is why I recommend two separate QMS procedures. The first would be “Control of Outsourced Processes,” and is a simple table with two columns: the first column lists the outsourced processes, and the second column lists what controls you flow down to the provider. For example:

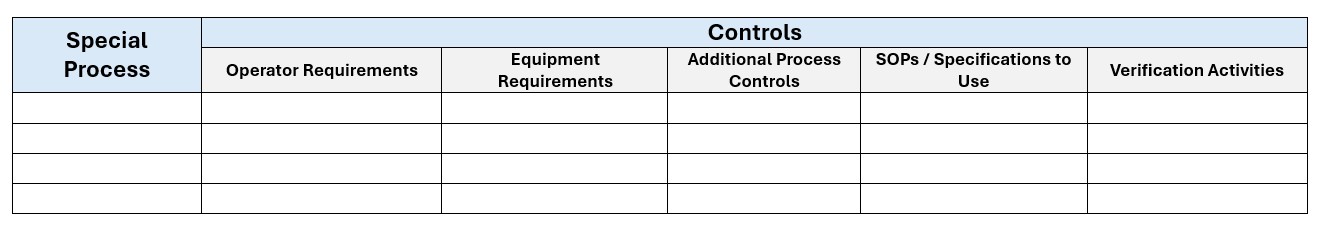

The second procedure would be called “Control of Special Processes.” In this case, you might have a table with multiple columns, indicating the controls over personnel, equipment, environment, and even the required specification to use for each of the listed special processes. It might look like this:

You might then go back to the procedure Control of Outsourced Processes and, for any outsourced special process, just point to the Control of Special Processes as well, so it’s clear they are linked.

Christopher Paris is the founder and VP Operations of Oxebridge. He has over 35 years’ experience implementing ISO 9001 and AS9100 systems, and helps establish certification and accreditation bodies with the ISO 17000 series. He is a vocal advocate for the development and use of standards from the point of view of actual users. He is the writer and artist of THE AUDITOR comic strip, and is currently writing the DR. CUBA pulp novel series. Visit www.drcuba.world